Things Learned while Racing to Make a Sculpture

I was prancing along, playing with the multi-objective algorithms, wondering about polymorphism and jellyfish (see prev. post), when I realized that the Lumen Prize was due June1, which seemed like a good fit for the project. I hardly knew how the project would take form. I had three weeks and it seemed like a good fire to light under my own ass.

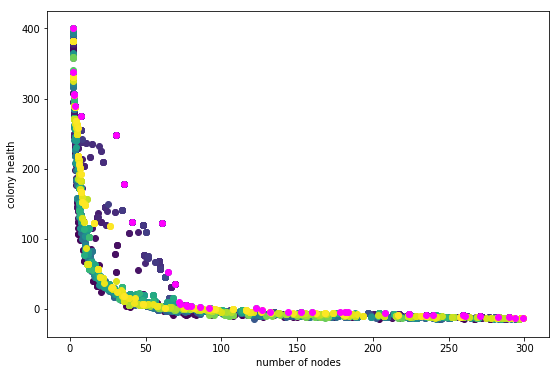

I ran a long evolution of 100 generations, hoping I would get some neat shapes that ‘embodied purpose,’ sort of the way a plant embodies the purpose of replicating its genes. I got this plot:

Dark blue to yellow is oldest to newest generations. Magenta is the all-time-best. The evolution was not evolving! Might as well have used a purely random search and saved the best finds. The whole draw of the evolutionary algorithm is to find incrementally better solutions to a problem. That wasn’t happening, and it felt silly to make a sculpture pretending it was.

After days of tweaking everything I could imagine, I discovered two major mistakes.

1- I was using the wrong pareto-frontier selection algorithm!

Two were supplied by DEAP: NSGA2 and SPEA2. All I knew was that both are supposed to select n non-dominated individuals from a population. Turns out NSGA2 doesn’t always work. Switched to SPEA2, populations got steadily better.

2- I was testing the fitness of a genome using a random environment.

The spherical nutrients moved randomly, and although the amount of randomness between tests was the same, the specific motion of the particles was not identical. It is as if the ‘weather’ was different each time I tested an individual. This meant that a slightly more fit individual in one generation might be less fit in the next generation. Since the algorithm operates by selecting the most fit individuals, even if they are only slightly more fit, and searching for improvements on those individuals, it can get stuck never improving. To fix this I simply ran one test per indvidual and fixed the random seed, which is like taking the weather of one day and fixing it so it happens the same way everytime.

The second issue I spent tons of time fiddling with, and realized that for these evolutionary algorithms to work (in the sense that they find better solutions than what they started with), there is an essential criteria. The variation between fitness of one genome, if it is being tested multiple times, must be small compared to the variation between fitness of different genomes. If the fitness evaluation is deterministic and only happens once, this is a non-issue.

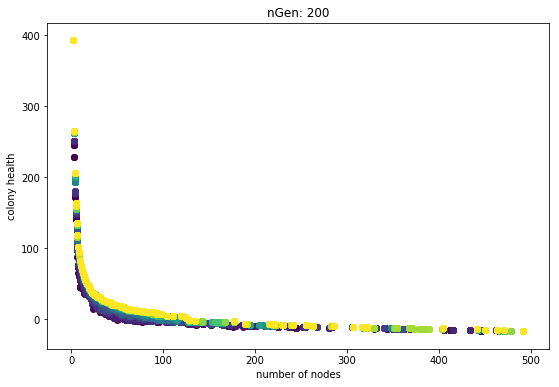

Here is a plot using SPEA2 and one fixed-seed fitness test per genome:

The generations are always slightly better than the previous. Sure they get hung up, and it seems like the rate of improvement slows down, but the main point is that they each generation is never worse. The problem of getting stuck is a weakness of objective-based evolutionary algorithms. That’s why I have plans for trying some techniques like novely search.

I find it telling that only after I grapled with the second issue did I sort out the first, more underlying problem. Dear self: inspect the basic assumptions and simplest factors first! Anyway, it may be interesting to re-run the algorithm with non-deterministic fitness tests and see if the evolution can make progress. It is likely any progress would be slower, with more backward steps.

Summary

- Use SPEA2 not NSGA2

- Make sure variation between multiple tests of one genome is small compared to variation between different genomes.